From: http://blog.springsource.com/2011/01/04/green-beans-getting-started-with-spring-mvc/?__utma=1.539753019.1311656113.1313390018.1313460563.5&__utmb=1.2.10.1313460563&__utmc=1&__utmx=-&__utmz=1.1313460563.5.5.utmcsr=baidu|utmccn=%28organic%29|utmcmd=organic|utmctr=spring&__utmv=-&__utmk=250182278

,

a part of the core Spring Framework, is a mature and capable

action-response style web framework, with a wide range of capabilities

and options aimed at handling a variety of UI-focused and non-UI-focused

web tier use cases. All this can potentially be overwhelming to the

Spring MVC neophyte. I think it's useful for this audience to show just

how little work there is to get a bare Spring MVC application up and

running (i.e. consider my example something akin to the world's simplest Spring MVC application), and that's what I'll spend the rest of this article demonstrating.

I'm assuming you are familiar with Java, Spring (basic dependency injection concepts),

and the basic Servlet programming model, but do not know Spring MVC.

After reading this blog entry, readers may continue learning about

Spring MVC by looking at Keith Donald's Spring MVC 3 Showcase, or the variety of other online and print resources available that cover Spring and Spring MVC.

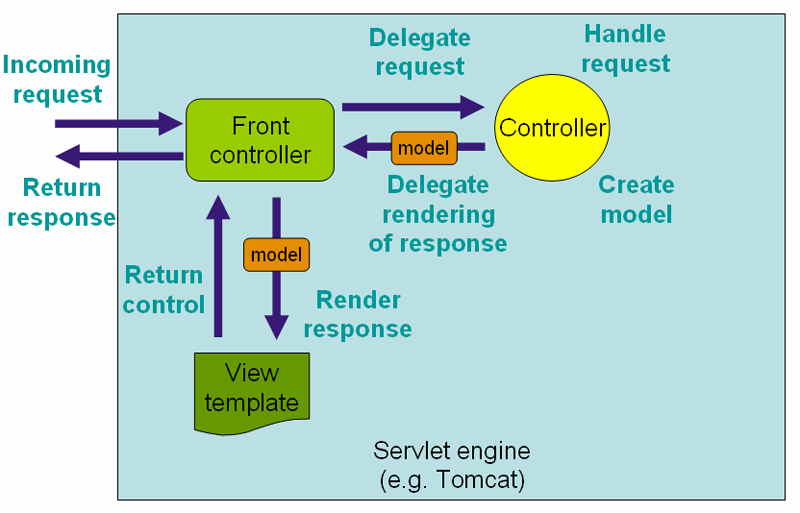

Spring MVC includes most of the same basic concepts as other

so-called web MVC frameworks. Incoming requests enter the framework via a

Front Controller. In the case of Spring MVC, this is an actual Java Servlet called DispatcherServlet. Think of DispatcherServlet as the gatekeeper. It doesn't perform any real web or business logic, but rather delegates to POJOs called Controllers where the real work is done (either in whole or via the back-end). When the work has been done, it's the responsibility of Views to produce the output in the proper format (whether that's a JSP page, Velocity template, or JSON response). Strategies

are used to decide which Controller (and which method(s) inside that

Controller) handles the request, and which View renders the response.

The Spring container is used to wire together all these pieces. It all

looks something like this:

Bootstrapping the DispatcherServlet and Spring Container

As mentioned, all incoming requests flow through a DispatcherServlet.

Like any other Servlet in a Java EE application, we tell the Java EE

container to load this Servlet at web app startup time via an in the web

app's WEB-INF/web.xml. The DispatcherServlet is also responsible for loading a Spring ApplicationContext

that is used to perform wiring and dependency injection of managed

component. On this basis, we specify some init parameters to the Servlet

which configure the Application Context. Let's look at the config in web.xml:

WEB-INF/web.xml

| 04 | xsi:schemaLocation=" "> |

| 09 | org.springframework.web.servlet.DispatcherServlet |

| 12 | /WEB-INF/spring/appServlet/servlet-context.xml |

A number of things are being done here:

- We register the DispatcherServlet as as a Servlet called appServlet

- We map this Servlet to handle incoming requests (relative to the app path) starting with "/"

- We use the ContextConfigLocation init parameter to

customize the location for the base configuration XML file for the

Spring Application Context that is loaded by the DispatcherServlet,

instead of relying on the default location of -context.xml).

Wait, What if Somebody Doesn't Want to Configure Spring via XML?

The default type of Application Context loaded by the

DispatcheServlet expects to load at least on XML file with Spring bean

definitions. As you'll see, we'll also enable Spring to load Java-based

config, alongside the XML.

Everybody will have their own (sometimes very strong) opinion in this

area, but while I generally prefer-Java based configuration, I do

believe that smaller amounts of XML config for certain areas can

sometimes still make more sense, for one of a number of reasons (e.g.

ability to change config without recompilation, conciseness of XML

namespaces, toolability, etc.). On this basis, this app will use the

hybrid approach, supporting both Java and XML.

Rest assured that if you prefer a pure-Java approach, with no Spring

XML at all, it's pretty trivial to achieve, by setting one init param in

web.xml to override the default Application Context type and use a variant called AnnotationConfigWebApplicationContext instead.

The Controller

Now let's create a minimal controller:

| 01 | package xyz.sample.baremvc; |

| 03 | import org.springframework.stereotype.Controller; |

| 04 | import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RequestMapping; |

| 07 | * Handles requests for the application home page. |

| 10 | public class HomeController { |

| 12 | @RequestMapping(value = "/") |

| 13 | public String home() { |

| 14 | System.out.println("HomeController: Passing through..."); |

| 15 | return "WEB-INF/views/home.jsp"; |

Let's walk through the key aspects of this class:

- The class has been annotated with the @Controller annotation, indicating that this is a Spring MVC Controller capable of handling web requests. Because @Controller is a specialization of Spring's @Component Stereotype

annotation, the class will automatically be detected by the Spring

container as part of the container's component scanning process,

creating a bean definition and allowing instances to be dependency

injected like any other Spring-managed component.

- The home method has been annotated with a @RequestMapping annotation, specifying that this method should handle web requests to the path "/", i.e. the home path for the application.

- The home method simply logs a message to system out, and then returns WEB-INF/views/home.jsp,

indicating the view which should handle the response, in this case a

JSP page. (If hardcoding the entire view path including WEB-INF prefix,

and the fact that it's a JSP, seems wrong to you, you are right. We'll

deal with this later)

Now, we need to create the view. This JSP page will simply print a greeting.

WEB-INF/views/home.jsp

| 01 | <%@ taglib uri="" prefix="c" %> |

| 02 | <%@ page session="false" %> |

Finally, as previously mentioned, we need to create a minimal Spring Application Context definition file.

WEB-INF/spring/appServlet/servlet-context.xml

Let's examine the contents of this file:

- You'll note that a few different Spring XML namespaces are being used: context, mvc, and the default beans

- The declaration ensures the Spring

container does component scanning, so that any code annotated with @Component subtypes such as @Controller is automatically discovered. You'll note that for efficiency, we limit (to xyz.sample.baremvc in this case) what part of the package space Spring should scan in the classpath

- The declaration sets up Spring MVC's

support for routing requests to @Controllers, as well as how some things

like conversion, formatting and validation are handled (with some

sensible defaults based on what (libraries) is present in your

classpath, and the ability to override if needed)

The web app is now ready to run. Assuming the Servlet container (tc

Server in my case) is set to listen on localhost:8080, starting the

application and then hitting the URL via our browser results in a display of the expected greeting:

As trivial as it is, running this application involves all the major

pieces of a working Spring MVC application. Let's walk through the major

sequences and component interactions:

- When the web app starts up, the DispatcherServlet is loaded and initialized because of the entry in web.xml.

- The DispatcherServlet loads an annotation-based Application Context,

which has been configured to scan for annotated components via a

regular expression specifying the base package(s).

- Annotated components such as the HomeController are detected by the container.

- The HTTP request to hits the servlet engine and is routed to our (baremvc) webapp.

- The implicit "/" path at the end of the URL matches the regex

that has been registered for the DispatcherServlet, and the request is

routed to it

- The DispatcherServlet needs to decide what to do with the request. It uses a strategy called a HandlerAdapter

to decide where to route the request. The specific HandlerAdapter type

(or types, since they can be chained) to be used can be customized, but

by default, an annotation-based strategy is used, which routes requests

appropriately to specific methods in classes annotated as @Controller, based on matching criteria in @RequestMapping annotations found in those classes. In this case, the regex on the home method is matched, and it's called to handle the request.

- The home method does its work, in this case just printing

something to system out. It then returns a string that's a hint (in this

case, a very explicit one, WEB-INF/views/home.jsp) to help chose the View to render the response.

- The DispatcherServlet again relies on a strategy, called a ViewResolver

to decide which View is responsible for rendering the response. This

can be configured as needed for the application (in a simple or chained

fashion), but by default, an InternalResourceViewResolver is used. This is a very simple view resolver that produces a JstlView which simply delegates to the Servlet engine's internal RequestDispatcher to render, and is thus suitable for use with JSP pages or HTML pages.

- The Servlet engine renders the response via the specified JSP

Taking It to the Next Level

At this point, we've got an app which certainly qualifies as the world's simplest Spring MVC application, but frankly, doesn't really meet the spirit of that description. Let's evolve things to another level.

As previously mentioned, it's not appropriate to hard-code a path to a

view template into a controller, as our controller curretly does. A

looser, more logical coupling between controllers and views,

with controllers focused on executing some web or business logic, and

generally agnostic to specific details like view paths or JSP vs. some

other templating technology, is an example of separation of concerns.

This allows much greater reuse of both controllers and views, and

easier evolution of each in isolation from the other, with possibly

different people working on each type of code.

Essentially, the controller code ideally needs to be something like

this variant, where a purely logical view name (whether simple or

composite) is returned:

| 03 | public class HomeController { |

| 05 | @RequestMapping(value = "/") |

| 06 | public String home() { |

| 07 | System.out.println("HomeController: Passing through..."); |

Spring MVC's ViewResolver Strategy is actually

the mechanism meant to be used to achieve this looser coupling between

the controller and the view. As already mentioned, in the absence of the

application configuring a specific ViewResolver, Spring MVC sets up a default minimally configured InternalResourceViewResolver, a very simple view resolver that produces a JstlView.

There are potentially other view resolvers we could use, but to get a

better level of decoupling, all we actually need to do is set up our own

instance of InternalResourceViewResolver with slightly tweaked configuration. InternalResourceViewResolver

employs a very simple strategy; it simply takes the view name returned

by the controller, and prepends it with an optional prefix (empty by

default), and appends it with an optional suffix (empty by default),

then feeds that resultant path to a JstlView it creates. The JstlView then delegates to the Servlet engine's RequestDispatcher to do the real work, i.e. rendering the template. Therefore, to allow the controller to return logical view names like home instead of specific view template paths like WEB-INF/views/home.jsp, we simply need to configure this view resolver with the prefix WEB-INF/views and the suffix .jsp, so that it prepends and appends these, respectively, to the logical name returned by the controller.

One easy way to configure the view resolver instance is to introduce

the use of Spring's Java-based container configuration, with the

resolver as a bean definition:

| 01 | package xyz.sample.baremvc; |

| 03 | import org.springframework.context.annotation.Bean; |

| 04 | import org.springframework.context.annotation.Configuration; |

| 05 | import org.springframework.web.servlet.ViewResolver; |

| 06 | import org.springframework.web.servlet.view.InternalResourceViewResolver; |

| 09 | public class AppConfig { |

| 11 | // Resolve logical view names to .jsp resources in the /WEB-INF/views directory |

| 13 | ViewResolver viewResolver() { |

| 14 | InternalResourceViewResolver resolver = new InternalResourceViewResolver(); |

| 15 | resolver.setPrefix("WEB-INF/views/"); |

| 16 | resolver.setSuffix(".jsp"); |

We are already doing component scanning, therefore since @Cofiguration is itself an @Component,

this new configuration definition with the (resolver) bean inside it is

automatically picked up by the Spring container. Then Spring MVC scans

all beans and finds the resolver.

This is a fine approach, but some people may instead prefer to configure the resolver as a bean in the XML definition file, e.g.

It's hard to make a case for this object that one particular approach

is much better than the other, so it's really a matter of personal

preference in this case (and we can actually see one of the strengths of

Spring, its flexible nature).

Handling User Input

Almost any web app needs to take some input from a client, do

something with it, and return or render the result. There are a myriad

ways to get input into a Spring MVC application, and a myriad ways to

render the result, but let's at least show one variant. In this simple

example, we're going to modify our HomeController to add a new handler

method which takes two string inputs, compares them, and return the

result.

| 01 | package xyz.sample.baremvc; |

| 03 | import java.util.Comparator; |

| 05 | import org.springframework.beans.factory.annotation.Autowired; |

| 06 | import org.springframework.stereotype.Controller; |

| 07 | import org.springframework.ui.Model; |

| 08 | import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RequestMapping; |

| 09 | import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RequestMethod; |

| 10 | import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RequestParam; |

| 13 | * Handles requests for the application home page. |

| 16 | public class HomeController { |

| 19 | Comparator comparator; |

| 21 | @RequestMapping(value = "/") |

| 22 | public String home() { |

| 23 | System.out.println("HomeController: Passing through..."); |

| 27 | @RequestMapping(value = "/compare", method = RequestMethod.GET) |

| 28 | public String compare(@RequestParam("input1") String input1, |

| 29 | @RequestParam("input2") String input2, Model model) { |

| 31 | int result = comparator.compare(input1, input2); |

| 32 | String inEnglish = (result < 0) ? "less than" : (result > 0 ? "greater than" : "equal to"); |

| 34 | String output = "According to our Comparator, '" + input1 + "' is " + inEnglish + "'" + input2 + "'"; |

| 36 | model.addAttribute("output", output); |

| 37 | return "compareResult"; |

Key elements in the new code:

- We're using another @RequestMapping annotation to make requests ending in with the path /compare to the new compare method

- We are expecting the caller to pass us the two String input parameters as part of the GET request, so we grab them via the @RequestParam

annotation. Note that we are relying on the default handling for this

annotation, which assumes that these params are required. The client

will receive an HTTP 400 error if they are missing. Note also that this

is just one way of passing in parameters to a Spring MVC application.

For example, it's easy to grab parameters that are embedded as part of

the request URL path itself, for a more REST-style approach

- We use our Comparator instance to compare the two strings

- We stuff the comparison result into the Model object under the key result, so that it can be accessed by the View. Think of a Model as a glorified hashmap, in simplest terms.

While we could have modified our exisitng view to also be used to

display the comparison results, we are instead using a new view

template:

WEB-INF/views/compareResult.jsp

| 01 | <%@ taglib uri="" prefix="c" %> |

| 02 | <%@ page session="false" %> |

Finally, we need to supply the controller with a Comparator instance to use. We have annotated the comparator field in the controller with Spring's @Autowired

annotation (which will be detected automatically after the controler is

detected) and instructs the Spring container to inject a Comparator into that field. Therefore, we need to ensure the container has one available. For this purpose, a minimal Comparator

implementation has been created, which simply does a case insensitive

comparison. For simplicity's sake, this class has itself been annotated

with Spring's @Service Stereotype annotation, a type of @Component

and thus will automatically be detected by the Spring container as part

of the container's component scanning process, and injected into the

controller.

| 01 | package xyz.sample.baremvc; |

| 03 | import java.util.Comparator; |

| 04 | import org.springframework.stereotype.Component; |

| 07 | public class CaseInsensitiveComparator implements Comparator { |

| 08 | public int compare(String s1, String s2) { |

| 09 | assert s1 != null && s2 != null; |

| 10 | return String.CASE_INSENSITIVE_ORDER.compare(s1, s2); |

Note that we could just as easily have declared an instance of this in the container via a Java based @Bean definition in an @Configuration

class, or an XML based bean definition, and certainly those variants

might be preferred in many cases for the greater level of control they

offer.

We can now start the application and access it with a URL such as

/compare?input1=Donkey&input2=do

to exercise the new code:

Next Steps

I've really only scratched the surface of what Spring MVC can do, but

hopefully this blog post has given you an idea as to how easy it is to

get going with Spring MVC, and how some of the core concepts in the

framework tie together. It may also be appropriate at this point to

mention that in the interest of making it easier to understand the core

concepts, there are a few (hopefully very obvious) areas in my sample

that are not handled the way they would be in a larger or production

application, as an example, the hard-coding of messages inside Java

code, or some of the package organization.

Now I'd like to encourage you to learn more about and experiment with

Spring MVC's full featureset and comprehensive capabilities in areas

such mapping of requests to controllers and methods, data binding and

validation, locale and theme support, and general ability to be

customized to handle pretty much all web tier use cases that fit the

action response model.

One valuable resource for you in this learning process is Keith Donald's Spring MVC 3 Showcase, which includes working code showing most of the capabilities of Spring MVC, that you can easily load into SpringSource Tool Suite

(STS) or another Eclipse environment and experiment with. As an aside,

if you are not familiar with STS, I should mention that it's a great

tool for experimenting with the Spring set of technologies, because of

it's great support for Spring and features like the out of the box

project templates. In , I show how to get going with a new Spring MVC application via an STS template.